The Restoration of Huysmans at Wrest Park

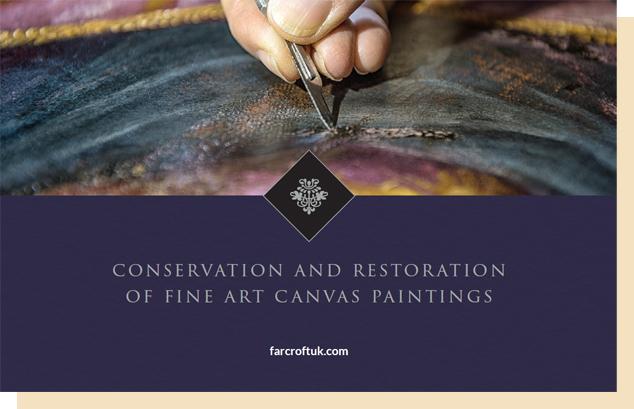

At the Farcroft Group, we are passionate about the need to preserve and protect our cultural heritage through the conservation and careful restoration of historic and important works of art.

We are not alone in our drive to see the country’s most beautiful and notable artworks brought back to their best; across the country there are numerous conservation teams within our historic country houses, stately homes and palaces working hard to restore great masterpieces and put them back on display for future generations to enjoy.

In this blog we go behind the scenes of English Heritage’s restoration of a group portrait by Jacob Huysmans (Jemima, Airmine and Elizabeth, daughters of Thomas, Second Lord Crewe of Stene), as conservator Rachel Turnbull and curator Peter Moore explain what it took to bring back this vital piece of Wrest Park’s history.

ABOUT THE PAINTING

A favourite of Catherine of Braganza, the wife of King Charles II, Jacob Huysmans became one of the most fashionable choices in the 17th century for aristocratic females looking for a portrait painter. His group portrait of three sisters – Jemima, Airmine and Elizabeth – who were daughters of Lord Thomas Crewe, Second Baron of Steane Park in Northamptonshire, was painted in around 1682.

Jemima would go on to marry Henry Grey, Duke of Kent, and become the Duchess of Kent. When the couple came to live at Wrest Park, she brought the painting with her, where it would remain for the next 200 years before being sold into private hands.

In 1917, following the death of her brother Lord Lucas during World War One, the then owner of Wrest Park, Nan Herbert, sold the house and all its contents at auction. The Huysmans painting was the third highest-selling lot in the Christies sale, selling for £504 (the equivalent of roughly £24,500 today).

The painting then disappeared from public view for the next century until, in 2016, it was gifted to English Heritage in lieu of inheritance tax and Wrest Park had the rare opportunity to re-acquire the painting for public display.

PAINSTAKING RESTORATION

Rachel Turnbull, senior collections conservator for fine art for English Heritage, recalls that, when it came into the studio, the painting was “in pretty poor condition, with a heavily discoloured and dirty varnish layer”.

What followed was around 300 hours of painstaking restoration to restore the 1.9m by 1.3m canvas to its former glory.

Turnbull said: “When we are restoring paintings, we treat each individual object as unique, and the treatment that we would take has to be unique to deal with that […] When a painting comes into the studio, the first thing that we have to do is have a really close look at it. We use lots of different forms of light, and all those different pieces of information come together to provide us with the answers to any questions we have.”

RESTORING THE PAINTING

Turnbull describes how her team’s evaluation of the painting revealed several areas for concern.

She said: “There is a seam down the right-hand side of the painting, where the artist would have stitched the canvas together, and there’s a lot of movement along that seam and flaking paint.”

The canvas also needed to be put onto a new stretcher, as its existing one – which was not the original – had warped.

Paintings of this era were usually varnished with natural resin, which would discolour and become very brown over time. This was another cause for concern, as Turnbull explains. “The varnish is so discoloured on this picture that it is actually disguising some elements of the composition,” she said. “We really wanted to bring back as much as we possibly can of these original really bright, vivid colours that Huysmans was famous for.”

HIDDEN DEPTHS

Once the heavily discoloured varnish had been removed, the beauty of Huysmans’ painting was revealed in all its glory.

“It’s a dramatic change,” Turnbull said. “The colours of the blue drapery and the lovely little rosy cheeks the sisters have got are absolutely adorable.”

An x-ray of the painting also revealed a hidden discovery that Turnbull explained had raised new questions among her colleagues. Speaking during the restoration process, she said: “We realised that there was a compositional change in the middle of the painting where a cherub has been disguised […] we don’t know whether the artist made this change or whether it was changed at a later date by a restorer.”

Subsequent investigations revealed that the cherub’s face was unfinished, suggesting that “the artist either changed his mind, or Thomas Crewe didn’t like the first composition”.

A PIECE OF WREST PARK’S HISTORY

The Huysmans painting is now back on public display at Wrest Park near Silsoe, Bedfordshire. It is one of very few items of the original collection to have been returned to the house during English Heritage’s tenure.

Dr Peter Moore, curator of collections for English Heritage, described the portrait’s return as “fantastic”. He said: “The painting is really important in terms of the history of Wrest Park, where not much of the original collection survives. So being able to bring this painting back into its ancestral home and show it to the public once more in the place that it spent so much of its lifetime is very special.”

For more information on Farcroft’s expertise in fine art restoration, please visit our fine art services, email enquiries@farcroftuk.com or call 0207 868 2420.

For additional information about fine art conservation and restoration read our ebook where we look into further science and art of conserving the artwork of history.

For additional information about fine art conservation and restoration read our ebook where we look into further science and art of conserving the artwork of history.